Paradise Lane

In the parable of the Good Samaritan, a Jewish traveller is stripped, beaten and left for dead at the side of the road. A priest and Levite come along and seeing him, cross to the opposite side of the road and pass by. Later, a Samaritan, a traditional enemy of the Jews comes by and seeing him takes pity. He bathes and binds his wounds, gives him his own cloak, places him on his donkey and takes him to an inn where he cares for him at his own expense.

Variations on the theme are to be found in all the major religions, where charity and compassion towards those who are suffering is rightly upheld to be one of our great human virtues.

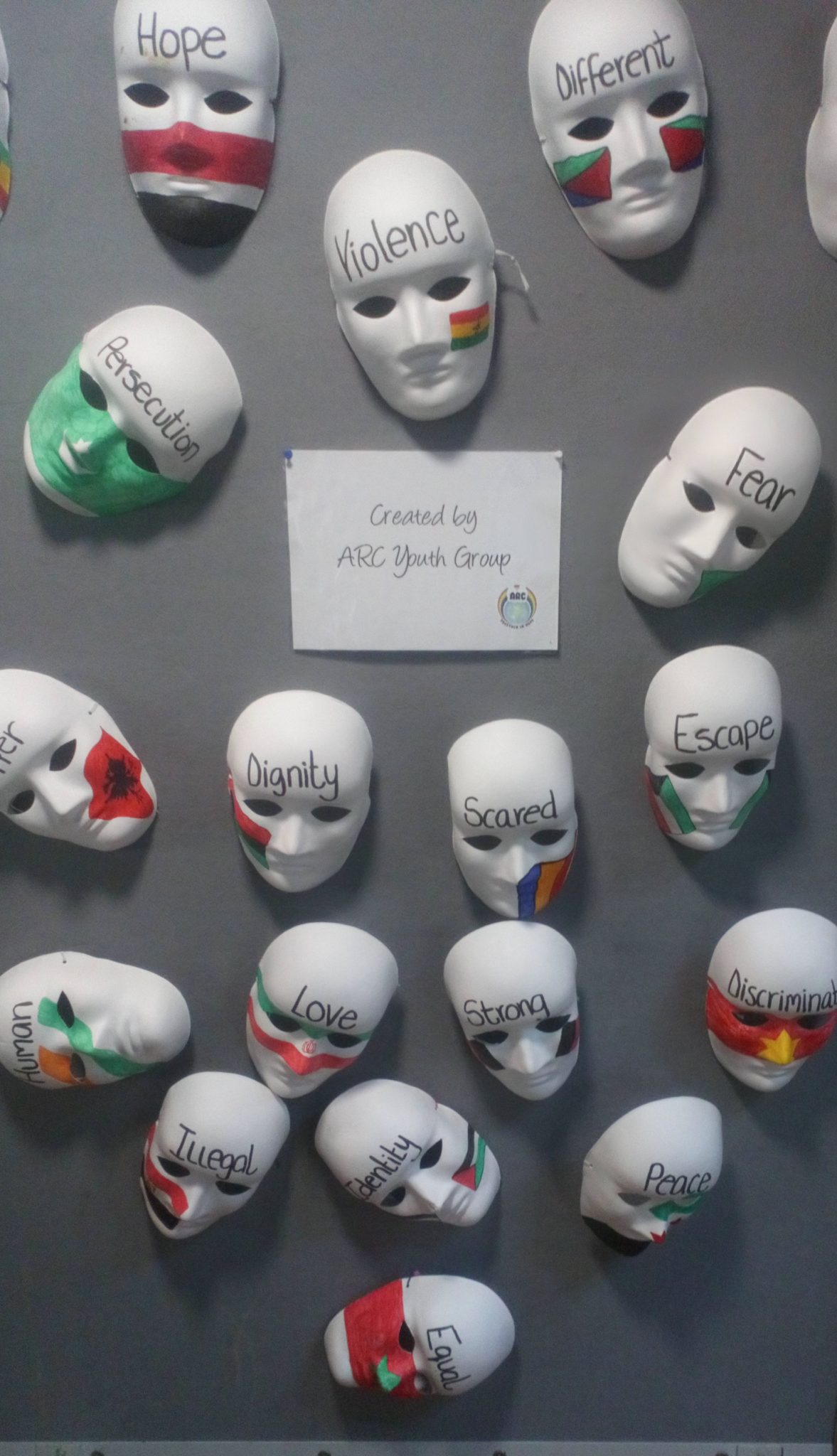

With this in mind it should therefore come as a surprise to learn that of the 1,237 towns and cities within the UK, less than twenty percent of those accept refugees and asylum seekers. Our great virtue has been politicised and despite the fact that refugees account for less than five percent of total migration into this country annually, they take up a disproportionate amount of negative publicity in the national press. My hometown of Blackburn takes in refugees and in order to better understand what is ultimately, a worldwide crisis, I’ve been spending time at the ARC Asylum and Refugee Centre on Paradise Lane. It’s been an enlightening experience.

There are twenty-five million refugees globally. People fleeing war, persecution, famine and poverty and each year a tiny proportion of those make their way to our shores. Having introduced myself to the group, I pinned a world map to the wall and using a felt pen asked them to mark their journeys. From Central America and China, through Africa and the Middle and Far East, the lines began to resemble a cat’s cradle crisscrossing the world.

Among them, an Afghan woman who escaped with her two young daughters after the Taliban came to the house and took away her eldest daughter, forcing her into marriage. Another Afghan woman trekked through the mountains with her family for fifteen days. When they got to the shores of the Aegean, they handed over what little money they had and put to sea at night in a rubber dinghy with over forty other passengers. During the night a boat pulled alongside and slashed the dinghy, sinking it. Most drowned, she and her family managed to stay afloat and were eventually picked up by a Greek patrol boat. I met a civil engineer from Syria who escaped through the mountains with his family when Isis attacked their town. An albino man from Africa whose seven-month journey took him through the jungle and Sahara Desert. A young family from El Salvador escaping violence, an old woman from the Congo, formerly Zaire, who remembered listening to Muhammed Ali’s Rumble in the Jungle on the communal radio in her village. One man pointed to the Mediterranean and said simply, “Graveyard.” So many epic journeys, so many stories, so much suffering. Most I spoke with hadn’t come here for a better life; they’d come here that they might live.

At the Centre, Sister Marie teaches English grammar, volunteers serve tea and toast while Syd and her assistants help with navigating the labyrinthine maze of paperwork: applications, rejections and appeals: the false summits of hope. A shuffling paper trail wending its way through our ponderous bureaucracy.

They are a mixed group of men, women and children of all ages. Some are embroidering a tapestry to present to the UN, with each stitch representing a refugee. They feel safe here. The town’s multi-ethnic population allows them to live quietly and begin rebuilding their lives. One Iranian man, a former political prisoner, questioned why anyone would want to live in London when they could live in Darwen? ‟Darwen” he declared ‟is beautiful.”

When refugee status is approved it automatically extends to their family. In poorer countries where resources are limited a family will select the strongest and fittest of the group, often a young male and pool their money, before sending him on the long arduous journey in the hope he’ll get through and help get them out. Very few, I learned, were single men as such.

And then I’m looking at the map of Europe and remembering back to the time when we were the EUs economic migrants. When unemployment hit three million in the early 80s, thousands of us took advantage of our Common Market membership and went to work on German building sites, in French vineyards, Dutch factories and Greek hostels and tavernas. Along with providing employment when there wasn’t any here, it opened our eyes to the world.

The map is making me restless and I find myself tracing my own journey. Through Deck Access and the Lodestar, past Green Lane and Mellor Brook: across the Irish Sea. I’m moving through Canada and Alaska, Australia and New Zealand, Malaysia, the Himalayas the Middle East and Africa. The countless paths, the twists and turns; the trajectory of a life that took me around the world before placing me here: a kindred spirit among fellow wanderers, at the ARC Refugee Centre, in the Methodist Mission on Paradise Lane.

Avoid Mother Kelly’s door step. You don’t know who’s been there.

Curly Whirly Swirly Things.

Maelstroms and hurricanes,

as exit holes in sinks and drains

suck on things material

as well as things ethereal.

Currents of the mental mists

also flow in arcs and twists.

Witches, Warlocks, stir love potions

mixing heartaching emotions.

Conflicting currents of the mind

where strange attractors blend and bind,

hopes, dreams, and aspirations

swallowed in radial gyrations.

All we see, think, touch and say

like patterns of forming dna

are doomed to dance where eddies sing

in curly whirly swirly things.

be cool at Yule.